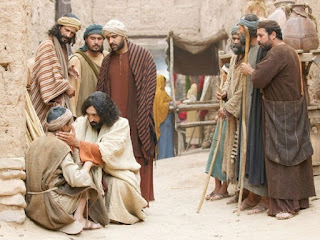

His disciples asked

him, “Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents?” May I speak to you in

the name of the G-d who creates, redeems and sustains us? AMEN.

Today’s Gospel presents

us with a puzzling story. In today’s lesson, as Jesus is leaving the Temple he encounters

a man born blind and his disciples ask him “Rabbi, was it this man’s

wrongdoing or his parents’ that caused him to be blind?”

To our modern ears,

that’s a strange question. But to people in the 1st CE Middle East,

it made perfect sense. The sins of the fathers often were seen as visited on

their children, sometimes for several generations, in the form of suffering.

Because we human beings do not handle notions of meaningless suffering well, it

is not surprising we attempt to assign blame for suffering somewhere. In this

case, it’s either the blind man himself or his parents whose sin is seen as the

origins of his blindness. So, which was it, they ask Jesus.

Either possibility is problematic. To say his parents’ sins had caused this man’s blindness suggests he is being unfairly punished for someone else’s deeds. His suffering is thus meaningless in any real moral sense. But, to presume he had done something to merit such extreme punishment as a lifetime of blindness requires Jesus to hold knowledge of a complete stranger he’s just met.

It also points to a deity

more prone to arbitrary punitiveness than anything loving. Whatever else that

god may be, it is not the loving Father Jesus so often references, the G_d who

makes the rain to fall on the just and unjust alike. In either case, this

practice of shaming a human being who is already suffering evidences no small

amount of sadism.

Sounds Familiar….

I have never found

Augustine’s teaching on original sin terribly compelling. Augustine argued that

a newborn child is born a sinner and will be eternally punished unless s/he is

baptized and later buys into the set of ideas that the western Christian church

has proclaimed everyone must hold. That’s simply not credible for those who

engage their faith with any degree of critical reflection. Anyone who has held

a newborn for even a couple of seconds knows that this beautiful tiny human being

bearing the divine image, just beginning its life, may be a lot of things but

sinner is simply not among them.

Augustine’s vision is a rather classic example of this “sins of the parents” thinking that Jesus is being confronted with here. Our original parents, Adam, whose Hebrew name means the human being, and Hava, whose Hebrew name means the mother of all living beings, were said to have inflicted their original sin onto all of their future progeny, according to Augustine.

[Image: Masaccio, Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, 1427]

Original Brokenness and

Its Wounds

Richard Rohr helped me locate that seed of truth in Augustine’s thinking with his notions of original brokenness. Unlike Augustine and the theologians spawned by his pessimistic reductionism who describe our world as “fallen,” Rohr, ever the good Franciscan, takes the Genesis account very seriously when it assesses the Creation at the end of the sixth day as “very good.” Not perfect. The Genesis writer simply says that the Creation - in all of its grandeur as well as its pain and suffering - is very good.

That said, we know there is pain and suffering in our world. And, like Jesus’ disciples in today’s gospel, we want to understand why that is. Rohr’s answer is simple: We are all born into families and societies where brokenness is part of the total picture present when we arrive. As such, we inherit all the woundedness that occurred before our births.

Over time, we become wounded ourselves and wound others. And it is this brokenness that we will in turn pass on to our children. And while G-d loves all of who we are, warts and all, brokenness and woundedness are unavoidable aspects of every human life and every human society.

So why don’t we just deal with our baggage? Why don’t our families just come to grips with their wounds? Why don’t our lawmakers create laws that repair our social world? Why must we pass this on generation after generation?

I think the answer is in front of us today. We inherit suffering and generate our own largely out of blindness. In some cases we know that our thoughts, words and deeds are harmful to ourselves and others. But in other cases, we are unaware that what we are thinking, saying and doing is wrong. In many ways, this is the most pernicious form of harm. As New Yorker reporter Hannah Arendt learned in covering the Nuremberg Trials of the agents of the Holocaust, true evil can come to be seen as normal, everyday, all around us. To an unconscious people, evil is invisible. As Arendt would put, evil can become banal.

An Unexpected Lesson

Many of us know that blindness personally. And as I offer my own story to illustrate that, I suspect some of you may relate to it.

When I was six years

old, my family moved to Bushnell over in Sumter County from Clearwater. This

small town was very different from the metropolitan area we had just left. And

so when we went to the courthouse downtown one afternoon for my Father to take

care of some business there, I quickly found myself on wrong side of the law and

social mores without even realizing what I had done.

Suddenly my Mother shrieked. “Stop!” she said, “You can’t do that, son! Come back here this minute.” I was shocked. I felt I was being punished for simply being the curious kid I always was. But there was something more to this, something darker, something unspoken. And so I asked the obvious question, “But, why Momma?”

I will never forget her

face clouding over at that moment. I thought she might cry. And she said, “Oh

son, I need to tell you some things.” She then began to explain the system

I would later come to know as Jim Crow. It was the first time I had ever been

aware of racism. I must confess that I did not make it easy for her, responding

over and over, “But, why Momma?” to which she finally said, “It’s

just the way it is, Son, and you will have to follow these rules if we are

going to live in this town.”

I do not believe that inherited brokenness and the wounds it causes are by definition sinful in themselves. None of us had anything to say about that. We arrived in a context already in existence. But what I do think is sinful is when the blind slips from our eyes and we begin to see our lives and our world clearly as they are and we do nothing in response. What is decidedly sinful is our insistence upon reimposing the blinds over our eyes because the truth makes us uncomfortable. And we compound that sin when we use the power of our governments to remove books from libraries and impose gag orders on teachers when that truth threatens to be told.

I have struggled with

the racism I inherited from my family and my society all of my life. And I will

wrestle with those demons, who often sneak up on me out of the blue, as long as

I live. I suspect the same is true for you as well. And if we are being honest

with ourselves, we will admit that this is but one of many forms of blindness

we wrestle with. In truth, in a time of rapidly changing understandings of

everything from the ways our lifestyles impact our planet to the way we

understand gender, we all have an awful lot of unlearning and relearning to do.

So let us begin by

being honest with ourselves. Losing the blindness that once shielded our

prejudices and the harms they do to the children of G_d is painful. It does

make us uncomfortable, as it should. But at some level that curse is also our

gift. The discomfort of cognitive dissonance recognizes what we teachers call

the teachable moment. It offers us an opportunity to learn, grow, mature, and become

more fully human.

This Sunday marks the mid-way point through the Lenten season. The church has designated this to be a time of reflection, introspection, of wrestling with our souls. Lenten lessons raise troubling questions: Where is the blindness in our lives? What is it that we don’t want to look at and yet know we must? Where is the brokenness in our lives? Have we dealt with it in a healthy way? Have we worked diligently enough to heal our wounds? And, if not, what brokenness and unhealed wounds might we be passing on to the next generation of souls coming to this world?

The consolation in all this wrestling with our souls is that we are never alone. G-d is present in all things. Our willingness to engage painful growth experiences is always met by G_d’s empowering and healing presence. And that is precisely is why we respond to all of those promises in our Baptismal Covenant with the words “I will with God’s help.”

I close with a Collect

we often use at the conclusion of our Prayers of the People. As I wrote this sermon,

it spoke to me in a new way and I hope it will to you as well:

Almighty God, to whom our needs are known before we ask: Help us to ask only what accords with your will; and those things which we dare not, or in our blindness cannot ask, grant us for the sake of your Son Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

[A sermon preached at St.

Richard’s Episcopal Church, Winter Park, FL, Sunday, March 19, 2023, Lent IV. You

may listen to the sermon as it was preached at the link provided below:

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Harry Scott Coverston

Orlando, Florida

If the unexamined life is not worth living, surely an

unexamined belief system, be it religious or political, is not worth holding.

Most things worth considering do not come in sound bites.

Those who believe religion and politics aren't connected

don't understand either. – Mahatma Gandhi

For what does G-d require of you but to do justice, and to

love kindness, and to walk humbly with your G-d? - Micah

6:8, Hebrew Scriptures

Do not be daunted by the enormity of the world's grief. Do

justly, now. Love mercy, now. Walk humbly now. You are not obligated to

complete the work, but neither are you free to abandon it. - Rabbi

Rami Shapiro, Wisdom of the Jewish Sages (1993)

© Harry Coverston, 2023

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

No comments:

Post a Comment